The LMS has nothing to do with learning

So where do we place an AI-based sense-giving chatbot?

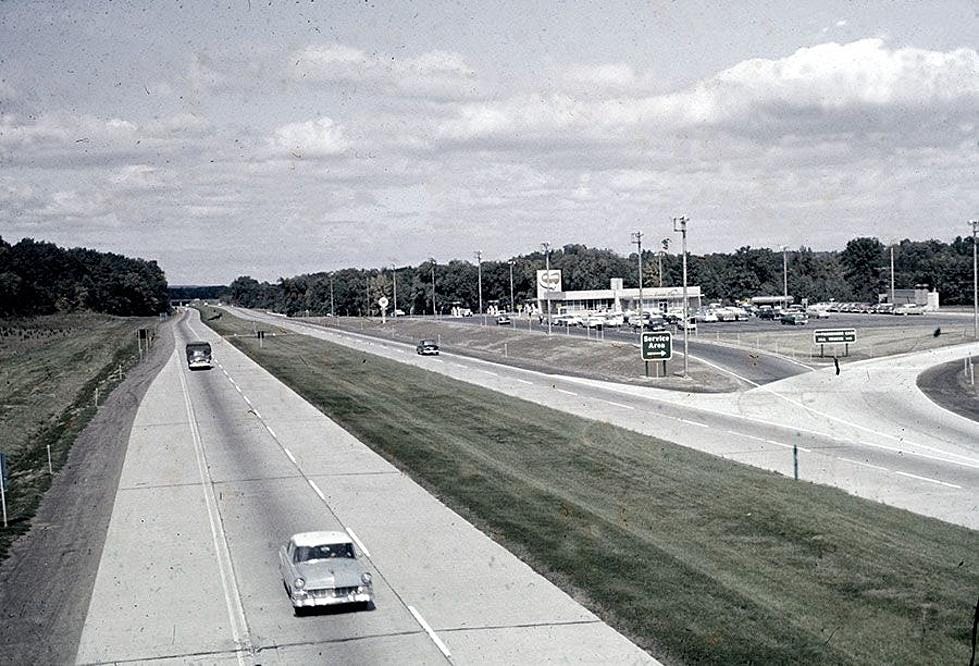

“Service Area from Thruway” via History of the Thruway Service Areas. Public Domain.

In a prior post, I described a user-based approach to developing integrated AI-based sense-giving chatbots for use in online education. In a recent discussion with Nectir AI CEO Kavitta Ghai, one of the questions we touched upon was “Where do we put them?” This question has been difficult to answer for a number of other Ed Tech LMS integrations, such as Zoom, Kaltura, Brainfuse, and so on. The difficulty stems from predicting when learners will need them (thereby placing the resource in proximity to the task) or where they are most likely to conveniently access them as a habit of mind (one consistent location). Do we place the resource in the permanent navigation, in the module area, embedded in the assignment prompt, or in a link that goes to a separate external location?

My contention here is that there is no good place to integrate an AI-based sense-giving chatbot in an LMS because the LMS was never designed as an application for learning – it has been and will always be a system for the administration of courses. As such, we cannot just look at the LMS as a visualized representation of the actual learning process and identify where learners most often encounter stopping points and seek information (and pin the chatbot to that location). It is similar to asking where to put a tourist information center along a highway – we are certain that travelers will need information at some point along the way but we don’t know exactly where nor when, and the interstate highway system isn’t designed to facilitate the unique itinerary of each traveler. The highway system is simply a “container” of infrastructure, not an “application” for fulfilling a traveling goal. Travelers must therefore accommodate their needs to the design of the system, as-is, rather than the system being designed according to how and when travelers need information.

And all of this is OK – this is not an indictment of the interstate highway system, nor the LMS as a course administration system. It is simply a statement to clarify that the LMS is not a learning application, and therefore implementing a learning tool to the LMS is more complicated than simply adding it to the LTI toolkit and saying “… we have now enhanced learning.”

Consider the following observations about LMSs, from a design perspective:

Print designers were the first Web designers: In the early days of browser-based worldwide web (www) user experience, the standard design of websites mimicked conventions drawn from print design: start at the top-left corner and work downward according to hierarchical content arrangements. The standard Web page layout reflected users reading Web pages as if they were reading a newspaper (a classic McLuhan example of filling the new medium with the old content). The “user journey” as a concept for application design had not yet been formulated.

The LMS is an expression of classic Web design: The LMS is visually consistent with plain vanilla, lowest common denominator Web design: vertically oriented content, hierarchically organized, permanent navigation, internal sub-navigation, pages, hyperlink and button-based click-through interfaces.

The LMS is an electronic proxy for campus-based education: The organizational structure of the LMS mimics the structure of campus-based program administration:

Courses classified according to discipline corresponding to similarly classified physical structures on campus.

Closed-ended course units corresponding to the concept of the semester.

Sub-sections (modules) corresponding to weekly classroom sessions.

Segmented units of study corresponding to book chapters.

Assignment start and due dates corresponding to classroom assessment.

Assembly of students in cohorts corresponding to classroom-based attendance.

I have worked with faculty over the years in numerous attempts to hack the Moodle and Canvas design concept to correspond with innovative instructional methods that transcend these constraints - all met with a conclusion that we have made more of a mess for learners than we have gained.

In contrast, mobile app developers, starting roughly in The Year of Our iPhone, 2007, benefitted from a development ecology that was unencumbered by the legacy of browser-based Web design. The user interface expanded in its grammar and visual semantics, horizontal and vertical scrolling extended concepts of spatial dimension. Most importantly, developers constructed the application environment according to patterns of the user’s journey, with continuous improvement through A/B testing, intense competition, and iterative updates. The app development philosophy became more analog (user-based) than traditional broadsheet design conventions.

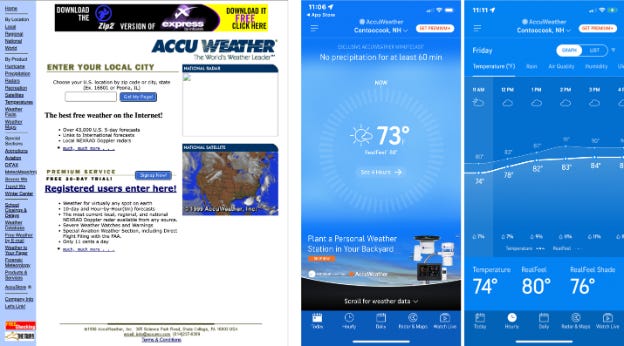

To illustrate the difference between an administrative and an analog approach to LMS design, consider the difference between the design of weather information in AccuWeather.com’s website from 1998 (left) compared to the current (2025) interactive design of its mobile app (right):

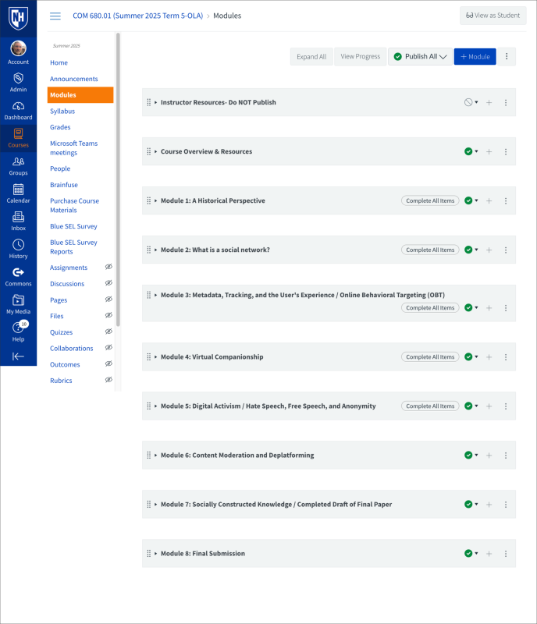

Now let’s look at a typical Canvas LMS course:

The current design of the Canvas LMS does not enable learners to “see themselves” in the information environment; the content is a mosaic that amounts to a picture of a course, not the subject matter; the arrangement of content corresponds to due dates, not the arrangement of meaning.

If the LMS were designed to correspond to the way humans actually learn, what would it look like? Perhaps the content would be arranged horizontally with progression from left-to-right, analogous to the progression of time? Or in a circular accretion pattern analogous to a coherent body of knowledge composed of various elements and layers? Or a schematic of a social structure representing the community of practice? As you can see, we have run into a problem: Which metaphor for learning do we adopt as a basis for visualizing the learning process?

My former instructional design colleague Elizabeth Dalton and I grappled with this question many years ago, which was a contributing inspiration for a terrific essay she wrote, “Metaphors We Learn By” (2015). Dalton’s theme centers on the premise that the language we use to convey the process of learning is often imbued with metaphoric characterizations of the subject matter, transfer, and cognitive processing, e.g. “passing along” ideas, “gears turning” in our heads as we think. The nouns and verbs we use to explain what happens when humans learn carry with them certain materializations of abstract phenomena to (over)simplify otherwise inaccessibly complex ideas. Dalton cites several seminal learning theories as metaphors:

Cognition in the learning experience involves storage in a mental space (knowledge as objects in a computing schema; knowledge as a construction).

Learning can be described as preparation for an expedition by becoming well-equipped for whatever may be encountered (ideas as places; knowledge as the ability to take on a social role in a group).

Ideas are born, evolve, blossom, and evolve (knowledge as a living organism).

Teachers often express what they do using behaviorist metaphors (knowledge as an object; transferred via words) with a minority expressing their work in situative or sociocultural terms (knowledge as a social construction).

The point here is that there is no metaphor that definitively and conclusively defines the process of learning such that we may build a singular learning application that is “analogous to learning” around it. (Nor is there a metaphor that is “wrong”). And this leaves us somewhat marooned in thinking how best to implement AI-based sense-giving chatbots, given the administration-oriented design of current LMSs and the lack of user-based alternatives. We may be relegated to placing the chatbot “at the borders” of the LMS, like tourist information centers adjacent to state borders.

Perhaps we should take a cue from the automotive industry which has recently come to an epiphany that touchscreen interfaces that take the driver’s eyes off the road might be a bad idea. They are reverting back to buttons and dials with an understanding that the affordances of a vehicle ought to reflect the primary use case – not the use of its accessories. Drivers seem to prefer having their controls where they can feel them.

If we imagine online learners in the metaphor of drivers of their education in the vehicle of the LMS, where would we place the “knobs” of the AI chatbot? In my propensity to think from a user-based position, perhaps we should ask learners.